Elsewhere, I write:

it is meaningless for me to separate out my work inside and outside the University from the work I continue to undertake on myself. It is meaningless for me to separate out my labour as something unique in the practice of my life.

After a decade in therapy I am moving to sessions every other week. For a long time I was having weekly sessions; for a long time I was having twice-weekly sessions; for some time I needed three sessions a week. The memory of all of this resonates; remembering why I needed this resonates. Who I was is who I am is who I will be.

I have written about this here, and here, and here, and here, and in all my writing about anxiety and the anxiety machine and alienation.

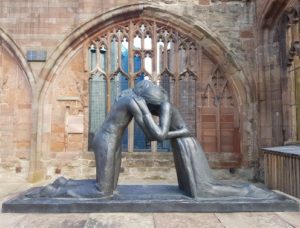

So it feels important to mark this agreement to move to sessions every other week. I feel compelled to sit with the importance of this. It is a very significant moment for me in my movement towards myself, and it carries with it all sorts of emotions, rooted in loss, grief, possibility, hope and peace. I see the early years of therapy about discovering or recovering or witnessing my courage and faith in myself, with the middle years doing some things that were focused upon finding justice for myself, and it is now that I can work through hope towards finding some peace. And this is repetitive in new ways and is never linear. In all this I continue to draw from my stories, and the emotional, relational, spiritual and cognitive knowledge they enable, as a well. I continue to reproduce those stories and new knowledge about myself in the world.

I also want to recognise the mutuality of this – I am very mindful of sitting with, and respecting my therapist’s position, care and love. I am mindful that there is a strong relational accountability between us. I am mindful of how this resonates across my relationships. Increasingly, I feel that I can recognise and respect this mutuality and solidarity, including with myself. I feel that the core of me lies in being accountable to my relations where that is possible, and that is a very beautiful thing.

I feel that there is a different moment of reconnection between me and the world. I see this in terms of the stories that have emerged through my work on myself. I also see this in terms of the places that I have sat in, the lanes that I have walked down, the roads that I have cycled, and the music that I have listened to, amplified in the last decade. This reconnection demonstrates to me that my work, practice, customs, values, life is not linear and that they are moving away from their assumptions.

Because I am letting go, I see the futility in my previous attempts to re-inhabit my own soul with the idea of being better or well; a newly-enclosed or commodified self. Rather, I understand why that belief or assumption was necessary for me for a while, in order to survive, but now I want to let go of my past assumptions and fetishes, and instead to think about myself in my relationships to me and others. There is something here about my sovereignty over my own story. There is also something here about my wanting to understand other people’s sovereignty over their own stories, and to try to learn from those. In this I take great strength from (indigenous and non-indigenous) stories and struggles for decolonising and dismantling and being inside-and-against-and-beyond (settler) colonialism.

So much of the therapeutic relationship is imminent to my life, my writing, my everyday practice, and the values that I carry forward. The decision to change the frequency of sessions has amplified this for me. To respect my position and my self-understanding, alongside my engagement with the complexity of the world and the communities/friends that I live and work alongside; I think that is enough.

I come back to stories because I remembered this quote from King (p. 32):

the truth about stories is that that’s all we are. You can’t understand the world without telling a story. There isn’t any centre to the world but a story.

I love this, because it articulates the validity of our own experience (and I am in acceptance of mine), and also what we have to learn from other people’s stories – it helps to understand our incompleteness and to create a richer, more storied relationship, rooted in dignity. This is trust in the sacred nature of journeying with others – to accept the risks, anxieties, possibilities. To honour relationships where possible; and also to accept that some relationships cannot work, and that I cannot be accountable to or in them.

And this is inextricably tied to my work as I consider my teaching. I will be working with first-year undergraduates on a new module, on evidenced-based teaching and learning.

In treating this module as a process, as being and becoming, I hope that we can generate new stories for people that respect the humanity of their places, philosophies, practices/practise, values and epistemologies.

I hope that the process we engage in will be focused upon knowledge production from the ground up, as lived experience, which connects people, stories and places in concrete ways.

I hope that we can understand how people and place form relationships that are accountable to each other in some way, which is constantly in negotiation rooted in care, dignity, duality, respect and responsibility.

I hope that we can engage with forms of thinking, acting, and being that emerge in relationship with decolonisation, so that we can imagine and embody our humanity, rather than enclosing and severing ourselves inside abstracted relations of domination.

I hope that we can generate thinking that refuses the assumptions of linear history, and of teleological, positivist narratives of development. In this, I hope that we can give voice to the ebb-and-flow between the past, present and future, and understand how this is rooted in ideological positioning that needs to be decolonised before it can be abolished.

I hope that we can create a module as a process that resonates with our lives, giving participants the power to make change, and to refuse the colonisation of other people’s lived experience, in particular through the imposition of idealised, white, male, able, cisnormative positions.

I hope that we can reflect on how our thinking and activity carries the possibility of care and/or harm, and potentially silences or gives voice to individuals and groups who are included/othered.

I hope that we are able to draw attention to dominant positions and modes of power, the ways in which hegemony is reproduced and recaptured as an ethical moment, so that we can hold a mirror up to power. This involves an engagement with knowledge, language, relationships, culture, so that we recognise our responsibilities as intellectuals, our positioning and that of others, so that intersections of privilege and non-privilege can be outed and reworked.

I hope that I am able to do the work necessary to enable my students to understand my story, in terms of this module, and that I am able to do the work necessary to understand their position. It is not good enough for us to demand that our students must do the work of travelling to our position. It is enough for us to engage with our students on their own terms, and to help them to find their own pathways that intersect their past, present and future.

I hope that we can be against utopian readings of the world. I hope that we can push towards “the next now”, which itself prefigures a better world. I hope that we can bear witness to each other’s legitimate movement in this process.

I hope that we can situate the reciprocity of relationships, and a variety of cultural positionalities, through storytelling and a recognition of the non-neutrality of language in its relationship to power and domination. Some of this is about memory and remembering; some of it is about generating new stories as we experience the module as a process.

I hope that we can experience the module as a decolonising pedagogic praxis; as a journey that refuses the inhumane reduction of our relationships to a risk-based approach to commodified pedagogic development.

I hope that we can develop epistemic range rather than epistemic enclosure, and enable each other to produce and recognise knowledge with the whole of our being – emotion, cognition, experience.

I hope that we can refuse deficit thinking about ourselves and others.

As Castenell and Pinar argue (p. 4):

we are what we know. We are, however, also what we do not know. If what we know about ourselves – our history, our culture, our national identity – is deformed by absences, denials, and incompleteness, then our identity is fragmented. Such a self lacks access both to itself and to the world. Its sense of history, gender and politics is incomplete and distorted.

My therapy playlist is here.

The bibliography that underpins this post is rooted in my attempts to appreciate narratives for decolonising and of indigeneity.

Ahmed, S. (2012) On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Arday, J., and Mirza, H.S. (eds 2018). Dismantling Race in Higher Education: Racism, Whiteness and Decolonising the Academy. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bhambra, G. (2017) Brexit, Trump, and ‘methodological whiteness’: on the misrecognition of race and class. The British Journal of Sociology, 68 (1): 214-32.

Bhopal, K. (2018). White Privilege: the myth of a post-racial society. Bristol: Policy Press.

Byrd, J.A. (2011). The transit of empire: Indigenous critiques of colonialism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Calderon, D. (2014). Speaking back to manifest destinies: A land education-based approach to critical curriculum inquiry. Environmental Education Research, 20 (1): 1-13.

Clark, I. (2018). Tackling Whiteness in the Academy. https://tinyurl.com/yct8qvp8

Goeman, M. (2013). Mark my words: Native women mapping our nations. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

The Human, Social, Political Sciences (HSPS) Cambridge Graduates and Current Students (2018). Decolonial Reading List (2018-2019). https://tinyurl.com/yd2se387

Joseph, Tiffany and Laura Hirshfield. 2011. ‘Why don’t you get somebody new to do it?’ Race and cultural taxation in the academy. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 34 (1): 121-41.

Salmón, E. (2012). Eating the landscape: American Indian stories of food, identity, and resilience. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Smith, L.T. 1999/2012. Decolonising methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. Lyndon: Zed Books.

Steinþórsdóttir, F.S., Heijstra, T.M. and Einarsdóttir, P.J. (2017) The making of the ‘excellent’ university: A drawback for gender equality. ephemera: theory and politics in organization, 17 (3): 557-82.

Tuck, E., and Guishard, M. (2013). Un-collapsing ethics: Racialised sciencism, settler coloniality, and an ethical framework of the colonial participate treat action research. In T.M. Kress, C.S. Malott, and B.J. Portfilio (eds), Challenging status quo retrenchment: New directions in critical qualitative research. Charlotte: information age publishing, 3-27.

Tuck, E. And Yang, K.W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education and Society, 1 (1), 1-40.

Tuck, E. And Yang, K.W. (2018). Series Editor’s Introduction. In Tuhiwai Smith, L., Tuck, E., and Yang, K.W. (eds), Indigenous and Decolonizing Studies in Education: Mapping the Long View. London: Routledge, x-xxi.

Tuhiwai Smith, L., Tuck, E., and Yang, K.W. (eds 2018). Indigenous and Decolonizing Studies in Education: Mapping the Long View. London: Routledge.

Wilson, S. 2008. Research as ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Blackpoint: Fernwood Publishing.