Last week’s CERD conference on doing and undoing academic labour got me thinking about whether anything, once done, could be undone. Or whether, once our labour had transformed some thing or some place or some outlook or some one, there was no undoing. No going back. Shakespeare has Lady Macbeth tell Macbeth in Act 3, as he is consumed by guilt after the killing of King Duncan, “Things without all remedy Should be without regard: what’s done is done.” Later in Act 5, as she in-turn becomes haunted and has to regard those things have that have beeen done and for which there are deep and human consequences, Lady Macbeth laments that “What’s done cannot be undone.” Ambition, guilt, shame, humanity, each pivoting around action and reflection.

This had me wondering whether ravelling and unravelling was a better metaphor for academic work or labour than doing and undoing. And whether the ravelled or tangled or complicated nature of academic work inside and beyond the academy might be untangled or decomposed as a set of threads that might then be re-stiched into something else. Or whether by highlighting one of the tangles, in my case educational technology, we might be able to use that unravelled element for some other purpose. One of the ways in which those other purposes might be described is in understanding the neoliberal networks in which the threads are tangled, and as a result in situating educational technology in networks of power and resistance.

However, a series of increasingly complicated, contextual factors makes the process of unravelling a more tangled operation.

FIRSTLY: On political economy: Spain. The two visualisations noted by ZeroHedge in their Brussels… We Have A Problem posting, highlight that the risk-controlled, growth and employability-obsessed strategies that underpin the new normal in UK higher education take no account of the depth/accute-nature of the global crisis. ZeroHedge previously described this wider context in terms of European Bank solvency deficiency, which involves

very scary numbers that were noted in Zero Hedge yet which barely received any mention in the broader press. Because the numbers were all very, very large (think eyes glazing over 11-12 digits large), and because their existence meant that the long-term, chronic pain for Europe, which is and has been one of public (and selected private) sector deleveraging (which oddly enough is called “austerity” by everyone to no doubt habituate people to associate debt reduction with pain – where is “mean-reversionism” when you need it?), … were promptly buried.

Our political economic and sociological illiteracy makes me reflect more-and-more on the false consciousness endemic in our academic labour. Do we really reflect on the true nature/context of our work? This illiteracy does our students and our staff no favours, because if Spain goes, all bets are off. Our focus on participation, personal learning, employability, marketised skills development or whatever, is cast in the shadow of this crisis and our illiteracy.

SECONDLY: On political economy: the UK as a de-developing nation. Larry Elliot in the Guardian has amplified how our political economic illiteracy affects HE policy and practice, and what we are willing to discuss or fight for inside the academy. He notes that Britain is a de-developing nation, and this has huge ramifications for higher education policy and practice.

In the hundred years from 1914 to 2014, the century since the outbreak of the first world war, the UK will have declined from pre-eminent global superpower to developing country, or “emerging market”. The symptoms of this vertiginous plunge in the world’s rankings are already starkly apparent: a chronic balance of payments deficit, a looming shortage of energy and food, a dysfunctional labour market, volatility in economic growth and a painful vulnerability to external events.

Since the start of the crisis, the UK has borrowed more in seven years than in all its previous history. It has impoverished savers by pegging the bank rate well below the level of inflation, and indulged in the sort of money-creation policies normally associated with Germany in 1923, Latin American banana republics in the 1970s and, more latterly, Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe.

Then there is the large number of unproductive workers engaged in supervisory or “security” roles, on the streets, in public parks, on the railways and at airports. There are the wars fought without the proper resources to do so, and the awareness among military commanders that, in the absence of any military conflict, their forces will be shrunk further, there being no attempt objectively to assess the nation’s enduring defence needs. There is the ramshackle infrastructure existing in parallel with procurement contracts that run billions of pounds over budget and are then cancelled.

This is the actually existing world for which we claim we are preparing our graduates.

THIRDLY: on risk. Andrew Haldane of the Bank of England’s Financial Policy Committee has argued that the modelling and risk—management systems that we have used in econometrics and financial services/financialisation has not respected the non-linearities, the self-organised criticality of systems nor the widespread risk of contagion across systems that exist in the real-world. He argues that the real-world displays non-normality that makes the highly-organised tolerances imposed by new public management a recipe for crisis. Our models are, in a word, unresilient. He notes that

It is not difficult to imagine the economic and financial system exhibiting some, perhaps all, of these features – non-linearity, criticality, contagion. This is particularly so during crises. Where interactions are present, non-normalities are never far behind. Indeed, to the extent that financial and economic integration is strengthening these bonds, we might anticipate systems becoming more chaotic, more non-linear and fatter-tailed in the period ahead.

Normality has been an accepted wisdom in economics and finance for a century or more. Yet in real-world systems, nothing could be less normal than normality. Tails should not be unexpected, for they are the rule. As the world becomes increasingly integrated – financially, economically, socially – interactions among the moving parts may make for potentially fatter tails. Catastrophe risk may be on the rise. If public policy treats economic and financial systems as though they behave like a lottery – random, normal – then public policy risks itself becoming a lottery. Preventing public policy catastrophe requires that we better understand and plot the contours of systemic risk, fat tails and all. It also means putting in place robust fail-safes to stop chaos emerging.

We do not stop to consider what this means for academic labour or for the practices of higher education. In our subject-silos, chasing our latest technology, and focused on marketised metrics and performance indicators, our academic labour-in-capitalism reinforces our intellectual enclosure.

FOURTHLY: on the political economy of UK Universities. Andrew McGettigan has developed work on HE financing, including some recent work on bonds. He argued:

Last year, the economist David Blanchflower, a former member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee, wrote in favour of universities issuing bonds.“In a recession, borrowing long term at low rates of interest is an eminently sensible thing to do— it is a classic Keynesian response,” he argued. “The public sector can utilise the savings of the nation. This is a time to invest at low, long-run rates of interest. Bonds could allow universities to borrow money for important projects cheaply.”

Universities have taken note. Many are now taking a closer look at bonds according to the British Universities Finance Directors Group, BUFDG… Banks say there is scope for universities to easily borrow another £4 billion whether through bonds or bank lending, much more even than the fabled cut in the Higher Education Funding Council for England’s teaching grant.

If the current upheaval in higher education does prompt a new wave of borrowing, then the consequences for universities could be equally huge. For borrowing on this scale comes with strings attached. Experience in the US, where bonds are more common, shows that those strings are capable eventually of transforming not only the daily life of a university but its very purpose.

McGettigan goes on to note how this then implicates Universities in the mechanics of the market through engagement with credit-ratings agencies or private finance initiatives/special purpose vehicles to leverage private investment. In this Universities are increasingly implicated inside neoliberal webs of practice, that include such special purpose vehicles, holding companies, joint venture companies, third party assurance companies and bondholders. These webs of complexity and risk are then formed inside the mess that is UK higher education policy where:

Some institutions may wish to avoid becoming trapped under what the University Alliance mission group has described as the £7,500 “cliff edge” defined by the level of tuition fees at which government quotas on student numbers start to bite. This could prompt them to start spending in a bid to justify higher fees to students… The common factor among all such strategies is that they are likely to require substantial up-front investment. Which is where bonds could come in.

Critical here is the extent to which University managers are willing to leverage institutions and the sector. McGettigan quotes Chris Hearn, head of education at Barclays Corporate, saying that “Time and time again we hear back from investors that they would desperately love to get their hands on anything to do with the university sector”. So academic labour is enmeshed within a world that is increasingly framed by credit ratings, leverage, private finance, hedge funds and private equity, with little space to critique the processes and lived reality of what is being done to the university system and individual institutions. This is important given the experience of “the University of California [which] has $13bn of bond debt and has pledged the tuition fees of generations of future students to maintain its AAA rating.”

There are, of course, institutional and regional disparities, as this piece in the Times Higher demonstrates, and HEFCE’s announcement of recurrent grants and student number controls further highlights the disparities between Universities that will come to rely more on external sources of income, including philanthropy and business partnerships, that in-turn affect the purpose and practices of those Universities. At issue then are: what do we know of the political economy of universities? What can be fought for inside the academy? For what purpose is our academic labour? Inside our subject-driven, NSS/REF-enforced silos, do we have the literacies and the courage to unravel the reality of higher education and to fight for something different?

FIFTHLY: technology as a crack through which the University is corporatised. Both Andrew McGettigan and I drew attention to the formation of Pearson College, its technological underpinnings, and the partnerships that it has with established academic institutions. My point was to show how that corporation was leverage gains from the higher education market, through its College, its educational think-tank, partnerships with universities like Sunderland and Royal Holloway, the role of Edexcel and the development of accreditation for profit, and the role of military accreditation in the United States. Diane Ravitch writes eloquently about this in the USA on her blog [search for the Pearson tag].

As competition hots-up in the squeezed middle of universities, as the government uses secondary legislation to lever open the sector for privatization and the market, as other providers are encouraged into the sector often using the promises of study using technology as a catalyst, an architecture is opened-up that threatens any reality of higher education beyond the profit motive. Thus, Pearson can call upon proprietary technology/LMS, established and culturally-accepted systems thinking, access to content, and deep market capitalisation, in order to open-up the sector for wider marketisation.

Pearson College highlights how educational technology is a way-in both to the extraction of value from universities, and to the recalibration of the purpose of universities to catalyse such extraction further. The focus here is on efficiency and business process re-engineering, and of a view that as technology is neutral, and offers simple efficiencies, who could argue with public-private partnerships aimed at such developments? There is no alternative, and the inefficient, unproductive public sector is ripe for restructuring through the services of corporations. Partnerships and leverage are enforced, in-part, because academic labour is shackled inside the demands of performativity revealed in the REF or NSS scores.

Moreover, a surfeit of new providers cheapens the bulk of academic labour that is not developing proprietary knowledge or skills, and will drive down labour costs and increase precarious work. Flexibility, redundancy, productivity, privatisation, restructuring, value-for-money, all underpinned by technology, become the new normal. As the discipline of fear enters the market, the space to develop literacies for critiquing the take-over and recalibration of the University is enclosed and suffocating.

SIXTHLY: the power of academic labour. All this emerges within the context of a global economic crisis that has no promise of resolution. The question is how academic labour can subvert, dissent from or push-back against the contexts and realities outlined above, either inside or beyond the University? Can academics find collective forms that enable the development of discretionary power? Can academics use their labour to overcome how that labour inside capitalism overcomes all of human sociability, to the point where all we can discuss is driven by growth? Can we develop new forms of labour in new spaces? Can the complexity of higher education be unravelled and re-stitched against this new public management?

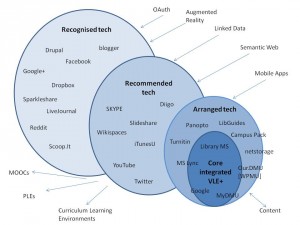

The University is a new front in the attempt by capital to further accumulation and the extraction of value. In that space technology reveals the conjuncture of forces that seek to catalyse and co-opt this process, in the services, technologies and applications that blind us to the social and economic realities. In that same moment technology enables to us to shine a light on what our academic labour might be for. What it might help us to defend, against its use for labour management, business-process re-engineering or the real subsumption of our labour for the valorisation of capital. Our uses of technology might usefully then be developed tactically and in public, where we identify how, in spite of their notionally free affordances many technologies are a back-door route for surveillance and militarisation, albeit sometimes non-consciously.

We might then ask, to what uses of technology did we say no? Where such uses are immanent to the institution were we able to say no? Are we able to identify possibilities for the use of technology that are precluded by new public management, and to identify why that is the case? How might cracking, hacking or modding the university, and doing so in public, help us to forge a new form of sociability or new spaces for higher learning?