“What if things are going to be absolutely fine?”

Me to myself, sometime towards the end of therapy, after years of asking “are we okay?”

Sticker on street furniture near the Pompidou Centre. It took me a while to remember that I exist. It took me a while to believe that I deserve to exist.

NB It feels important to note that there are some alternative routes you can take around managing your own mental health, and that support is available from a range of organisations including Mind (I had a good experience of therapy in 2000 with Mind in Darlington), Relate and Samaritans. Of course, there will be a range of possibilities for people with a range of life experiences. My point here is not to advise.

ONE. Sharing the wealth?

I left therapy after a decade in May 2019. It was the right thing to do and happened on my own terms, although it was negotiated over a long period with my therapist. This integrative and humanist therapeutic relationship helped me to save my life. It enabled me to hold and contain myself as I relived past trauma, and as I experienced a second breakdown after my Mom’s passing.

I have been thinking about what I have taken from therapy into the world as we now experience it. I have also been thinking about how I would have coped/not coped had I still been in the eye of the storm (I would have found the switch to virtual therapy incredibly difficult, in part because the human is so important in the therapy room and I feel that is missing online).

This morning I saw a retweet about how difficult it is for many to access therapy, either because NHS-funded therapy is time-limited, focused upon cognitive behavioural methodologies (a herd immunity for the soul), and has long waiting lists, or because private therapy is too expensive (although some therapists will undertake pro bono work). The original tweet focused upon crowdsourcing advice for people who are struggling, and a call to ‘share the wealth’, as if the assets that define good mental health are resources to be accessed like those on the Commons.

I have always struggled with this kind of call, although I completely respect the intention that lies behind it. In the same way, I struggle with calls for people to focus upon a positive mental attitude, or to be mindful or resilient (or to engage in mindfulness so they can be more resilient), inside a world that is alienating, and where a corporeal and physical, viral, destabilising force has infected that world. Too often, I see these calls as short-termist, or as an attempt to suture an alienated Self so that it can cope in a world that is increasingly unliveable and toxic.

When I was in therapy, I had a sense that the work was operating on multiple levels. First, my embodied trauma and what had been, because we may be through with the past, but the past is not through with us. Second, the everyday, alienating reality of an unjust world, in which we have to sell ourselves over and over again, and watch as others are brutalised, exploited or expropriated. Third, the closing down of the horizon of possibility for life, given the politics of austerity, climate heating, ecosystem collapse, economic populism, and so on. Fourth, how to struggle for the alternative, at the level of myself, my communities and the world.

Now each of these levels have been infected and recalibrated by the virus. Whilst I give thanks that I have worked through my embodied trauma, and I am able to find the courage and faith to struggle against an unjust world, and to accept the enclosure of our futures whilst attempting to do the right thing, I grieve that this is not universally or equally experienced. This brings me back to the idea that we can share the wealth in terms of mental health, in-part because the process and journey through therapy is so individual (although hopefully experienced in a wider, communal ecosystem of friends, carers, families, communities), and in-part because the idea of equality or equal access under capitalist social relations is nonsensical because we are individuated (and measured in competition with each other).

For instance, we know that many precarious members of our communities, or those who are black or minority ethnic, are anxious about the role of the State during any lockdown as they are at other times. We know that, in spite of the work of mutual aid groups, local councils, voluntary action groups, and so on, people are separated and isolated, and lack the day-to-day support they need. We know that the State and corporate response is on business continuity, business resilience, maintaining some form of capital circulation through monetary intervention, so that productive capacity can be shored-up in the medium term. We know that care has been marginalised because we see how the State fails care-workers and health-workers. We know that those who are regarded as economically unproductive, with apparently lesser human capital (in terms of productive skills, knowledge and capabilities) or social capital (in terms of access to networks), and who are marginalised by dint of race, gender, disability, sexuality, will be further disciplined or ignored.

TWO. A struggle for hope.

With less access to private property, money and social resources, the idea that these individuals or groups can become more resilient through mindfulness or our sharing of well-being or mental health resources, ignores the question: resilient for what and for whom? Whose narrative is being centred? Whose narrative is being heard? These questions feel important because my experience of long-term therapy is that a more positive mental attitude can only emerge from a long period of denial, anger, sadness/depression/melancholia, grief or mourning, and acceptance, in a process that can take years. And as a white man working in academia, I did not have to struggle with everyday micro aggressions or forms of battle fatigue/PTSD on top of my past and present experiences.

So, when I think about sharing the wealth, I think about my own experience as someone who needed intensive therapy (sometimes multiple times a week), with a consistent (flawed) human being, over a decade. It is my own experience of unpacking those layers of self, self in an unjust-capitalist-world, self in a world with an enclosed future, and self-in-struggle. What I write below is not designed to make the situation seem hopeless for those experiencing or living with distress under Covid-19, or those attempting to help. We have to struggle for hope in a world that has been made hopeless. Rather, it is my own stock-check of what I have taken from my own experiences, in no particular order. I have carried these into the world as-is. I completely recognise that for many of us the future is not what it used to be, and that for many others the future was an impossibility.

Billboard near Oxford Road, Manchester. Says it all, really.

THREE. Some things that emerged along the way

- Therapy is the most painful and exhausting thing I have ever done Rethinking my life exhausts me and gives me hope. In this corona-crisis I remember that exhaustion and pain. I know that we have been here before. If I could survive my life to this point, I can survive the Corona-crisis.

- Therapy demands courage and persistence. I went through a long and tortuous process of giving up and re-finding the hope that I would recover myself. At times, all I had was the courage to persist and to believe that it might be different. It feels no different now as I continue to redraft how I remember the past and how I imagine the future.

- I am amazed at what I continue to learn about myself, as I reflect. In this corona-crisis I am learning anew about my body, my mind, my relationships and networks, my community, and the world as it turns. I continue to learn about how to be at home with myself. I continue to think about intimacy and solitude, as opposed to despair and loneliness. It took a decade to get to this, and there is no algorithm for it, just a persistent self-awareness.

- Therapy enabled me to remember to internalise how caring my therapist is, and thereby to try to care for myself. The therapeutic relationship helped me to reveal the various sides of my self as they moved through space and time, and to change my life. I learned to self-soothe and to contain how I felt, rather than allowing it to overflow and overwhelm me. Sometimes I find this reality overwhelming, but it has enabled me to centre self-care as much as I can, because if I am not going to care for me in this moment, then I cannot care about others. Self-care includes understanding how and why I have a tendency to self-harm, including obsessing and overworking. I am always trying to remember that I am responsible for how I feel in every moment of my life, and to contain that feeling.

- The revelation of my life makes me weep. In each of these life experiences, I remember myself, and call myself out, and call how I feel to my attention, and I respect my humanity, so that I can respect the humanity of others. The corona-crisis is an opportunity for revelation about myself, my relationships, and how I see the world and then struggle for another. I know that I am privileged in this, and I attempt to share my wealth by helping others to hold themselves and their feelings. This is the site of my struggle for another world – to communalise my experience in therapy through my relationships as a long-term process.

- Sometimes you meet the most amazing people who hold you whilst you rage; and whilst you weep; and whilst you disintegrate. Because therapy is about disintegration and reintegration. And in processing the fear and rage and grief and disintegration, the reintegration has no blueprint. Some stuff will be reintegrated and some will be discarded or stored. This moment is no different to that of a year ago, notwithstanding I cannot hug my friends or see my Nan or go to a football match. This is still life, and recognising and valuing who is in my heart, or over a wall, or at the end of the phone, or in the pub or coffee shop in nine months time, is important. This helps me to do the work of sharing my wealth by holding others, metaphorically and emotionally and dialectically.

- Feeling is everything. Acknowledging feeling is everything. Reducing the cognitive content, and respecting how I feel is everything. It took a long time for me to go with the feeling, and to sit with the feeling, and to trace its contours and its lineages. Sometimes staying with the feeling is fucking impossible, because it hurts too much. My Mom’s death taught me this in spades. For too long in my life, the fear, anxiety, grief, anger were displaced. In spite of this, I make sure that I acknowledge and respect and listen to how I feel. Those around me have to get used to my occasionally drawing their attention to their feelings.

- Even though I had to manage my way through various crises in therapy, I always needed to recover my six year-old self. My six year old self kept me safe for a long time. Therapy was about honouring him. I remember him throughout this Corona-crisis. He is my guiding light.

- Therapy reminded me that I love being hugged, and to hug. I know that this will be possible once more, and that I must persevere – to persevere is everything.

- Therapy reminded me that I needed constant reassurance. I have to give myself reassurance, although perhaps not quite so much these days, because I accept that the future was never some fixed utopia. And I accept now that I am (good) enough.

- Therapy taught me about loss, and had a pedagogy focused upon recovery from loss by making sense of it, so that I can live. I am so glad that I was in therapy with this therapist during my Mom’s illness and passing. I take those practices into this Corona-crisis, and as a result I remember not to frame everything around loss. There is so much more to life than loss.

- Therapy taught me not to abandon myself. I deserved to be the world after therapy. It is important not to abandon myself, my values and my struggles in this Corona-crisis. In particular, it is important not to abandon myself because I feel forgotten. I try to let others know that they are not forgotten and that they are in my heart.

- Therapy is a process and it is not linear. Life is not linear. I did not know this in my heart until I was in very deeply. Now I see my life as a process, unfolding in countless, indeterminate and determinate ways, through myself, my loved ones, my communities and this world. What matters is the concrete: the lived reality of place and people. The Corona-crisis is part of that unfolding, and we must struggle for what makes sense to us, rather than the abstract ways in which people and institutions (including families) exercise power. This means a rejection of certainty, a weighing up of options, and an ability to live with the consequences of my own decisions (be they going to a pharmacist for a friend or not seeing my Nan or approaching my work in a different manner). Moreover, as my life unfolds in a non-linear way and is a process, I work to trust that good enough is good enough.

- Because this is an ongoing process of life, acknowledging a shifting feeling is everything. It is okay for me to be anxious or depressed, although I have worked through much of that now. Moreover, it is okay to remember where this anxiety or depression might take me, and it is okay for me to feel my way out of those feelings, rather than being anchored in melancholia. I try to do this by remembering and knowing myself. This is why the reductionism of a positive mental attitude or mindfulness is a struggle for me. I always struggled with the idea that behavioural practices could work on their own. Therapy taught me that my most important doing was related to knowing, remembering, honouring and respecting my being as I tell it out. The process of my life is doing, knowing and being as a movement.

- Therapy taught me that sometimes all I can do is hold on for tomorrow, even when sometimes existing from minute-to-minute feels fucking impossible. Persevere.

- Therapy taught me about my networks and relationships, that it is okay to give some up when they are not nurturing and are one-sided, and do not give to us. However, it also taught me to keep doors open wherever possible, and to accept the shades of grey, the give-and-take, the imbalance at times. It taught me about my friendships, and who I need to be there at 3am. This is no different now.

- Therapy is about love. In these times it is important to remember love, and even in our anger at the situation and the injustices and the exclusions and the marginalisations and the pain, to situate our response around our love for ourselves and the world we wish to create. There is no possibility without love.

THREE. Reconciliation.

Remembering these things, and in particular centring myself and the love I have felt in my life feels crucial in making decisions. These include the decision not to visit my Nan again. She is 60 miles away and extremely vulnerable. She brought me up for a while and is the light of my life. I have had 18 extra months with her since her fall and as her dementia worsens, and I see this extra time as a blessing. I mourn not being able to visit her, but I have been grieving her for a while. In missing her, I celebrate our relationship anew.

Likewise, my Dad and my Father-in-Law who are also extremely vulnerable. They are also too far away and need to self-isolate. They also need networks around them, which is an impossibility in the world we have made. This world we have made and the ways in which it exacerbates vulnerability are part of the reason I am so angry about this Government’s response to the Corona-crisis, and in recognising how our leaders condemn our families through their actions and omissions and carelessness, I remember what we must struggle for.

This also gives me the courage to refuse the implication to be productive. To learn new skills that will make us better human beings. Instead, being in long-term therapy whilst holding down my job and doing some voluntary work, taught me to find ways to prioritise mourning or grieving. I recognise my privilege in this, and that others will be drawn towards anxiety. I use my time in therapy to draw attention to this: How can there be business-as-usual? As my self comes under strain, and the virus infects and inflects my relationships, I am constantly reminded that the strains are secondary to my work, and they are potentially additive to my concerns over our ecosystem. Therapy taught me to have the courage to weep and shake my head, and to have faith in the validity of that response.

I know that there is much grief coming. Yet, I also know that this carries a significant potential energy. This energy will be driven by how I feel, but it will also be centred around relationships that I have kept open, when they might have been closed down. This energy is not simply negative and in relation to loss. It also means maintaining the potential for love beyond loss and grief and apparently hopeless positions. It means weeping and shaking my head as acts of solidarity.

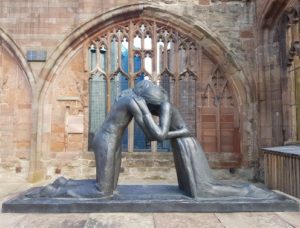

The Reconciliation Statue at Coventry Cathedral. This is all there is.

FIVE. From each, to each.

It is through the courage of my six year old in staying in the game that I can validate my faith in myself, and move towards some form of justice in this world. Through therapy, justice was centred around being heard and validated; upon reconciliation rather than reparation. In each of the crises in my life, there has been no chance of hope or opportunity for peace, because there has been no justice and no reconciliation with the past or present. As a result, I can accept that the future is not what it used to be. The world-as-is, is not the world we thought it would be. Maybe it is not the world we wanted or hoped. My struggle will be for the hope that this world becomes more possible for more people, rather than more austere and impossible for most. However, I am reconciled to the improbability of this possibility.

One of the outcomes of therapy was an understanding of how far I had come, not only in the present and how I live my life, but also in reconciling myself with my past. Moreover, this is a constant reminder to think through what power I do have, and how to use it for self-care as a process of collective care. Having had two breakdowns and long periods of chronic fatigue, in which my body forced my mind to stop making me run and run, I realised that I had to acknowledge what power is available to me. I only give up this limited power when I think I don’t have any at all, and in this moment my doubts swamp my belief. I had to learn to forgive myself a few things.

And so, what might be termed a positive mental attitude took a decade to coalesce or to take a form through which I could leave an intensive and intimate therapeutic relationship. In this coalescing or reforming, I took the energy of the therapeutic relationship as a mode of hope in my own life. Yet I recognise in this my own privilege in being able to pay for this work and the expertise that enabled it. It was an expensive, painful and exhausting decade that enabled me to feel and then to realise that whilst I had never been scared to die, I was no longer scared to live.

I am not sure how sharing the wealth helps with this for those who are isolated, made marginal, suffering structural oppression or exploitation, or in abusive relationships. Perhaps it is all we have in these days of social isolation, when we cannot hold each other physically close and we have limited mental stimulation. We know that the uncertainty is incredibly stressful, and that the psychology of isolation is damaging to our physiology as well as our psychology. Finding any port in a storm demands new connections, possibilities and hopes, and some form of mental and physical activity. Finding any mechanisms for controlling our existence, like establishing a routine, however limited in nature, is crucial. And here I am privileged again because I have a yard in which to sit, a partner, a mutual aid group, a roller for my bike, some t’ai chi I can do, I have books and writing, and 10 years of therapy in the bank. I have resources, activities and some control.

Maybe mindfulness or CBT techniques are better than nothing; that said, over time our collective and individual PTSD will require much more. When we have moved to our new position, we also need to recognise how our way of building the world and our social metabolism with the world has left us so mentally and physically vulnerable. This capitalist society has left shockingly paid people to keep the wheels turning, and to cope with deaths in hospitals and care homes. It has left people with limited resources to have to make decisions that put themselves and others at risk. It has left us divorced and separated from each other and the world, in a dystopian solitary confinement. It has left us so depleted that we are sharing CBT tricks on Twitter and building from the bottom as a just-in-time form of social solidarity. This demands our recognition now so that after-the-fact we can struggle for an intercommunal, intersectional and intergenerational alternative, centred around our humanity and celebrations of our differences. Because the virus has amplified the horrendous, alienating reality of capitalist social relations, and we deserve to live rather than to scrabble for survival.

It is the power of long-term, collective commitments that offers a new hope and a new shared wealth based on unequal individual and collective lives. In this way, I see my therapeutic experience as part of a wider ecosystem that I hold and to which I contribute, and that is shifting and moving. In this way, my thinking about mental health, ill being and moving beyond, replicates some kind of facilitated, mutual aid, in which survivors, self-help groups, voluntary organisations, friendships and professionals develop some alternative practices for-life that can be open to all. From each according to their ability. To each according to their needs.

Hold on to the love that you know//You don’t have to give up to let go

Deadmau5 feat. Cascade, I remember.

Banner, Finsbury Square, Occupy LSX.